- Home

- Shlomo Kalo

THE CHOSEN : The Prophet: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 2)

THE CHOSEN : The Prophet: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 2) Read online

THE CHOSEN

By

Shlomo Kalo

Book II: THE PROPHET

© All Rights Reserved

Y D.A.T. Publications POBox 27019,

Jaffa 6127001, Israel

Email: [email protected] www.y-dat.co.il

More about and of Shlomo Kalo here: www.y-dat.com

THE CHOSEN SERIES

Original Hebrew title: HaNivchar (The three books in one volume)

4th Hebrew edition, 2011

3rd English print edition, 2014

First Kindle edition 2015

English translation by Philip Simpson

Cover design: Hagit Shani. Image: kwest/Shutterstock

ISBN: 978-965-7028-51-3

THE CHOSEN print editions are available in English, Hebrew and Korean

No part of this book, except for brief reviews,

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means electronic, digital or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording or by any

storage or retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the Publisher

…In the previous part of THE CHOSEN

Book 1: The Youth

“The Chosen” is a novel based on the Biblical story of Daniel, and Book One gives an account of his early years. The narrative opens with the aftermath of the conquest of Jerusalem by the armies of Nebuchadnezzar, King of the Chaldeans. A group of Jewish youths is to be sent to Babylon, to serve in the court of Nebuchadnezzar, and Daniel and his close friends, Mishael, Hananiah and Azariah, are among those selected. He has time for a final visit to the prophet Jeremiah, who gives him his blessing, and must then part from his mother and his younger siblings and join the convoy. (His father was killed in the last battle in the royal palace of Jerusalem, after the king had fled.)

The convoy proceeds on the long and tortuous journey from Jerusalem to Babylon, with various adventures along the way, blended with reminiscences of the past. Daniel has particularly fond memories of Nejeen, his sweetheart since childhood. During this journey he hears for the first time eyewitness accounts of his father’s death and also strikes up some unlikely friendships, which will prove significant, such as that with Or-Nego, a senior Chaldean officer and commander of the convoy. A few other Jewish youths, especially Adoniah, develop hostility towards Daniel.

On arrival in Babylon the four friends are given new names (Daniel becomes Belteshazzar; Mishael, Hananiah and Azariah are now -- respectively -- known as Meshach, Shadrach and Abed-nego) and must be educated for their roles in the service of the King, learning the Chaldean language and the ways of the court, and honing their equestrian skills. This section of “The Chosen” ends when the four friends finally come face to face with Nebuchadnezzar himself and must answer his questions. While pledging to serve the King, Daniel insists that his first loyalty is to his Judean heritage. The King -- cruel and capricious though he undoubtedly is -- respects the young man’s principles and promises him a responsible position in the imperial administration.

Table of Contents

Book II: THE PROPHET

Nashdernach

In Mishael’s Lodging

The Tanneries On The Euphrates

On Figs And Nuts

Between The Walls

The Delegation Sets Out

The Man With The Dagger

Belteshazzar

I Am Your Servant

Without Making A Sound

Nejeen

Without Any Connecting Thread

Four Weddings

Jahanur

The Blazing Furnace

The Rebellion

In The Dead Of The Night

Adoniah

Book II: THE PROPHET

Nashdernach

Working in the office of Nashdernach, the man appointed by the King to supervise his senior counsellors and reputedly an authority on the holy writings of the Jews, was fraught with tension. Runners came and went from early morning till late in the evening, even at times when Nashdernach was absent from the office, leaving their messages either orally, in which case the duty clerk made a written record with a stylus on finely crafted scrolls, or in the form of inscriptions on clay tablets, parchment or those thin, flimsy sheets of paper imported from Egypt, made from reeds and known as “papyrus”.

For his part, the chief minister of the King’s council made every effort to be present and to receive in person the dispatches arriving from all far-flung corners of the great kingdom, especially the oral reports, which were sometimes corrupted in transmission from one runner to another and from one clerk to another. If he suspected any such inaccuracy, the minister would personally interrogate the runner and force him to repeat the message over and over again, while a harassed clerk took dictation. If the several versions of the same material were inconsistent, as frequently happened, or even contradicted one another, a less common occurrence, Nashdernach would fume, abusing and berating the unfortunate runner and the fool who had entrusted him with the message, and sending him back the way he had come, accompanied by a runner of his own, who was instructed to report the minister’s displeasure, demand an enquiry and return post haste with a clear and authenticated version of the original message.

At such times as this, the minister’s extensive office was in a ferment: scribes and calligraphers running back and forth in search of more efficient styluses and better quality parchment, anxious to avoid any mistakes when taking dictation from Nashdernach, runners waiting tensely and changing places in the line, depending on how keen they were to be sent to that distant region from which the corrupted message had originated, secretaries consulting scrolls and tablets in search of all available information regarding the governors and agents of the Crown responsible for that particular locality. There were quieter days too, days of routine when no unrest had been reported in any of the regions and the provinces on account of some or other demand on the part of the King or those governing on his behalf; no one was complaining of an unreasonably oppressive regime or fomenting sedition.

A constantly irksome matter, naturally enough, was the tribute paid by conquered lands. Governors, chosen by the local populace, and agents acting on behalf of the Chaldean monarch, would sometimes make common cause with the residents of that territory or region or formerly sovereign state, and try every means at their disposal, from exploiting obscure points of Chaldean law to the offering of bribes, in the effort to reduce the tax to what they considered a more tolerable level. Thus for example, the merchandise sent in accordance with the treaty of submission, signed by the envoys of the King and representatives of the population of the vassal state, was not always of the quality explicitly required by the terms of the treaty. On the contrary, all too often these goods were of inferior quality, sometimes very inferior quality, so much so that Nashdernach took it upon himself to return them to the sender with a reprimand, a warning or even a threat, and this in spite of the expenses involved in returning the goods. And there were duplicitous agents who resorted to covering the inferior commodities with a thin top layer of goods of superior quality. If someone confirmed receipt of the merchandise without adequate inspection and reported it satisfactory, then the conspirators in the provinces had cause for celebration, while the people of Babylon had no option but to consume the flawed foodstuffs, gritting their teeth and swallowing the bitter pill. In many such cases Nashdernach demanded a thorough investigation of the issue, and the clerk who confirmed the receipt faced dismissal. In cases where responsibility

was less easily assigned, the high quality material masking the inferior was simply sent to the palace for the use of the King and his court, and the remainder taken to the market and sold off cheaply – a highly unsatisfactory outcome. And if the business came to the King’s knowledge, someone would pay for his carelessness, with a heavy fine or a lengthy term of penal servitude.

He was noted for his attention to detail and his diligence, qualities for which Chaldean clerks were not always renowned and especially – for his honesty. Whenever it was revealed, this uncompromising honesty aroused admiration – closely followed by jealousy, scorn and rejection. Nashdernach appreciated these qualities and came to depend on him when he needed to take decisions or prosecute somebody or other.

He did his work conscientiously and did not skimp on the hours of work, often staying on late in the office if some matter required urgent attention. And with this too he gained the esteem of Nashdernach and the jealousy of his colleagues. Furthermore, his handwriting was clean and legible and he wrote with remarkable speed to the minister’s dictation which, in his angrier moments, tended to lack consistency and clarity, verging on the incoherent.

Late one evening a report of an imminent uprising in a remote southern province arrived on the minister’s desk, this on account of a demand for the doubling of the rice quota sent to Babylon as tribute. The effect of the demand would be to add still further to the already wearisome burden of toil at every stage of the process – planting, harvesting, sorting, drying, packing and dispatch to the authorities in Babylon.

Nashdernach decided to send a punitive expedition to ravage the province and reduce its “feckless” inhabitants, as he called them, to “poverty and penury”, and the only question in his mind was the scale of the expedition required, bearing in mind the expense involved and the need to obtain royal approval.

Nashdernach approached him as he was engaged in transcribing an illegible text onto clean parchment, gave him a sharp look with his oily, bloodshot eyes and asked him:

“Will one battalion suffice?”

“To start with,” he replied.

“What’s that supposed to mean – ‘to start with’?” – Nashdernach retorted, angry and surprised.

“The first act of suppression will only be the beginning,” he explained calmly, adding: “The revolt will spread, and people won’t bother rebuilding the straw huts that have been torched; instead they’ll set ambushes for Chaldean soldiers and attack them. This is their territory and they know all its dark corners, every tree and every stone, and if it comes down to guerrilla warfare the rebels will have the advantage and you’ll have to send another expedition, and then another.”

“In the end, the rebels will be crushed!” the minister declared, disbelieving the other’s words, despite the confident tone in which they were spoken.

Ignoring the interjection, he continued:

“And on top of everything, you’ll lose all the rice – all of it!”

“Expenses, expenses – and no revenue!” – Nashdernach grumbled.

Instead of answering, he went back to deciphering the ancient text.

The minister turned and began pacing up and down his spacious office, lit with numerous oil-lamps, his hands clasped behind his back. He was wearing a brown robe and a cloak of superior fabric, with no embellishment other than the silver medallion hanging on his chest, the symbol of his eminent status in the service of the King.

Having measured the length and breadth of his office once again, Nashdernach finally stopped by his desk and asked him:

“And what would you do in my place?”

“Without presuming to put myself in your place,” – he looked up and calmly met his supervisor’s gaze – “I would rescind the excessive demand for doubling of the rice quota.”

“What makes you say it’s ‘excessive’?” – cried Nashdernach.

“The rebellion that it’s provoked.”

“They’re just a bunch of idle no-hopers!” – Nashdernach complained.

“If they were idle no-hopers they wouldn’t have completed even the original quota, and they wouldn’t now be in such a mutinous mood, spoiling for a fight.”

“If I reverse the decision,” – the minister tried to explain – “I shall lose face in the sight of those barbarian populations, and they’ll try to wriggle out of their existing obligations! Other lands and provinces will learn from them and follow their example, and the whole apparatus will unravel, with disastrous results!”

“The opposite is the case,” he retorted evenly.

“How so?” his supervisor queried, a sceptical glint in his eyes.

“Only a strong ruler is capable of admitting his mistakes, and such an admission will arouse only esteem and respect in the hearts of the peoples under his sway. If you withdraw the excessive demand, you will gain the affection and appreciation of the local populations, and you will save the costs of a punitive expedition, and not run the risk of incurring royal displeasure. In addition, you will again receive the quota of rice as agreed in the treaty of submission, and it is very likely, that if you succeed in winning over the people of this province with incentives or expressions of your appreciation for their efforts – they themselves will decide to add to the existing quota, even if they don’t go so far as to double it.”

“You have a brain in your head!” exclaimed Nashdernach, clasping his fingers tightly behind his back. The minister turned sharply, sat down facing him and said to him:

“Listen to me, Belteshazzar! Put that work aside and listen!”

He did as he was asked, carefully folding the document and placing the work in progress under an ivory paperweight, then looked up at his supervisor serenely, his tranquil eyes cleansed from all the vanities of the world.

“Your advice is the best that there is, but that doesn’t mean that I have to accept it and put it into effect! Not at all!” exclaimed Nashdernach. “However sincerely we may wish to do what is right – we are compelled to act in ways contrary to honest reason. And why is this?” he asked, and continued his impassioned speech without waiting for an answer: “It’s because of the need to preserve this skin of ours,” – and he pinched the back of his mottled hand – “We are concerned for our skin because there’s no one who can be trusted! You have to understand – this idea, so logical and sensible, will be whispered in the ears of the King and presented in the most unfavourable light, as a sign of failure, the plan of an abject and spineless minister who can’t manage his own affairs and worst of all – it will be taken as a slur on the honour of the King and a token of flawed loyalty. Pay close attention to what I’m telling you,” Nashdernach stressed – “Disloyalty to the King, betrayal of the King’s trust, well, you know the rest! Hard labour for the remainder of your life, confiscation of property, wife, sons, daughters, parents – on the streets!” He struck the table with his fist, so hard that the stylus left on it leapt into the air and fell to the floor.

He bent down, picked up the stylus, replaced it on the table, and responded:

“The esteemed minister is gravely mistaken!”

“What is that supposed to mean?” – once again Nashdernach fixed him with that oily stare of his, expressing wonderment and considerable curiosity.

“There is someone who can be trusted.”

“Who?”

“God.”

The minister froze in his seat and his fleshy mouth gaped open, like the mouth of a fish. A long moment passed.

“Who is this God that can be trusted. Are you referring to Bel or to Marduk? They both have a habit of abandoning their devotees in times of adversity.”

“Neither one nor the other.”

“Who then?”

“The God who created everything, who rules over everything, and who loves us as a father loves his children.”

“And why then, if such a God indeed exists, who loves us as a father loves his children, and who created everything and rules over everything, why, I ask you, has

this father-God cast us down to flounder in this Hell?”

In his deep, limpid eyes, a bright glow flashed for a moment, and he answered the minister Nashdernach, senior counsellor to King Nebuchadnezzar:

“Because people don’t put their trust in him!”

Nashdernach pondered this, and after a long silence, he rose from his seat and resumed his pacing, back and forth, his step vigorous, hands clasped behind his back.

He returned to his copying work, and was on the point of finishing it, when Nashdernach called to him from one of the corners:

“And you trust in Him, who created everything and rules over everything, who loves us as a father loves his children?”

“With all my heart and all my might!” – was his clear and resonant response.

And sure enough, the minister Nashdernach changed his mind and decided against sending a punitive expedition. Instead he sent a deputation of conciliators who informed the inhabitants that the King, the valiant and the wise, the compassionate and the merciful had see their misery, and being well aware of their devotion to him and valuing their loyalty, he had decided to release them from the increased rice quota and even, in recognition of the respect and the warm feelings of esteem in which they held the King, to forgo the standard quota of rice for the current year, as a gesture of the goodwill, appreciation and gratitude that the King felt for them.

When the messenger-runner returned from the remote province he was so emotional he had great difficulty giving his report, describing how those unfortunate people had received the astonishing news, how they had hugged and kissed him and carried him shoulder-high, how they decided there and then, using their own meagre resources, to erect a temple to King Nebuchadnezzar, the wise and the valiant, the compassionate and the merciful, the one and only, and to worship him as a god, since only a god – those unfortunates claimed – could understand their feelings and the depth of their poverty, know of their oppression and bring it to such a conclusive and satisfactory end.

THE CHOSEN : The Prophet: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 2)

THE CHOSEN : The Prophet: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 2) THE CHOSEN: A Man Much Loved: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 3)

THE CHOSEN: A Man Much Loved: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 3) The Fantastical Adventures of Leutenlieb of the House of Munchausen

The Fantastical Adventures of Leutenlieb of the House of Munchausen THE CHOSEN : The Youth: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 1)

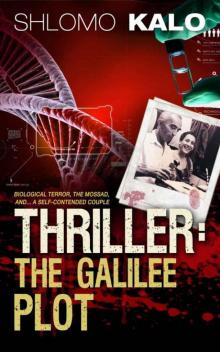

THE CHOSEN : The Youth: Historical Fiction (The Chosen Trilogy Book 1) THRILLER: The Galilee Plot: (International Biological Terror, The Mossad, and... A Self-contended Couple)

THRILLER: The Galilee Plot: (International Biological Terror, The Mossad, and... A Self-contended Couple)